Lessons from Pep Boys’ Aborted Attempt to Go Private

LBOs in recent years have involved financial sponsors’ providing a larger portion of the purchase price in cash than in the past.

Financial sponsors focus increasingly on targets in which they have previous or related experience.

Deals that would have been completed in the early 2000s are more likely to be terminated or subject to renegotiation than in the past.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

It ain’t over till it’s over” quipped former New York Yankees’ catcher Yogi Berra, famous for his malapropisms. The oft-quoted comment was once again proven true in Pep Boys’ unsuccessful attempt to go private in 2012. On May 30, 2012, after nearly two years of discussions between Pep Boys and several interested parties, the firm announced that a buyout agreement with the Gores Group (Gores), valued at approximately $1 billion (including assumed debt), had collapsed, a victim of Pep Boys’ declining operating performance. The firm’s shares fell 20% on the news to $8.89 per share, well below its level following the all-cash $15-a-share deal with Gores announced in January 2012. The terms of the transaction also included a termination fee if either party failed to complete the deal by July 27, 2012. The failed transaction illustrates the characteristics and potential pitfalls common to contemporary LBOs.

Pep Boys, a U.S. auto parts and repair business, operates more than 7,000 service bays in over 700 locations in 35 states and Puerto Rico. With its share price lagging the overall stock market in recent years, the firm’s board of directors explored a range of options for boosting the firm’s value and ultimately decided to put the firm up for sale. Gores was attracted initially by what appeared to be a low purchase price, stable cash flow, and the firm’s real estate holdings (many of the firm’s store sites are owned by the firm). Such assets could be used as collateral underlying loans to finance a portion of the purchase price. Furthermore, Gores has experience in retailing, having several retailers among their portfolio of companies, including J. Mendel and Mexx.

The transaction reflected a structure common for deals of this type. Pep Boys had entered into a merger agreement with Auto Acquisitions Group (the Parent), a shell corporation funded by cash provided by Gores as the financial sponsor, and the Parent’s wholly owned subsidiary (Merger Sub). The Parent would contribute cash to Merger Sub, with Merger Sub borrowing the remainder from several lenders. Merger Sub would subsequently buy Pep Boys’ outstanding shares and merge with the firm. Pep Boys would survive as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Parent. The purpose of this reverse triangular merger was to preserve the Pep Boys’ brand name and facilitate the transfer of supplier and customer contracts. The Parent also was to have been organized as a holding company to afford investors some degree of protection from Pep Boys’ liabilities. The purchase price was to have been financed by an equity contribution of $489 million from limited partnerships managed by Gores and the balance by loans provided by Barclays Bank PLC, Credit Suisse AG, and Wells Fargo Bank.

Upon learning that the Pep Boys’ reported earnings for the first quarter of 2012 would be well below expectations, Gores attempted to renegotiate the terms of the deal, arguing that Pep Boys had breached the deal’s agreements. With Pep Boys unwilling to accept a lower valuation, Gores exercised its right to terminate the deal by paying the $50 million breakup fee and agreed to reimburse Pep Boys for other costs it had incurred related to the deal. Pep Boys said the firm will use the proceeds of the breakup fee to refinance a portion of its outstanding debt.

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

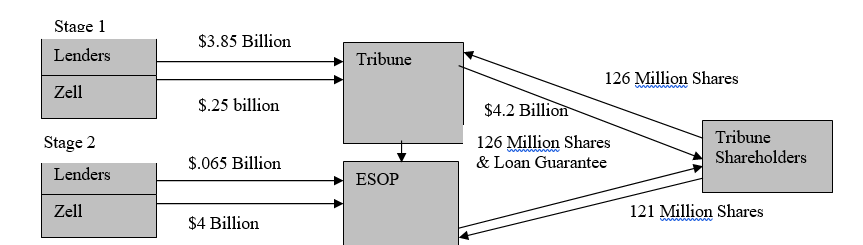

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 1).

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune’s board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

-Is this transaction best characterized as a merger, acquisition, leveraged buyout, or spin-off?

Definitions:

Direct Materials

Direct materials are raw materials that are directly traceable to the manufacturing of a product and are a component of the total manufacturing cost.

Fixed Overhead Rate

A predetermined rate used to allocate fixed overhead costs to cost objects, calculated at the beginning of a period based on estimated costs and activity levels.

Fixed Factory Overhead Volume Variance

The difference between the budgeted and actual fixed overhead costs attributed to variations in production volume.

Gross Profit

The financial difference between revenue and the cost of goods sold before other expenses are deducted.

Q4: A partnership or JV structure may be

Q11: What is the purpose of ultimately listing

Q26: In what way can the Comcast/GE JV

Q27: The M&A market for employer firms tends

Q62: Operational restructuring refers to the outright or

Q72: Split-ups and spin-offs generally are taxable to

Q91: Most M&A transactions in the United States

Q97: If the buyer believes that the seller

Q116: In calculating synergy, it is important to

Q139: Management may sell assets to fund diversification