Johnson & Johnson Uses Financial Engineering to Acquire Synthes Corporation

While tax considerations rarely are the primary motivation for takeovers, they make transactions more attractive.

Tax considerations may impact where and when investments such as M&As are made.

Foreign cash balances give multinational corporations flexibility in financing M&As.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

United States–based Johnson & Johnson (J&J), the world’s largest healthcare products company, employed creative tax strategies in undertaking the biggest takeover in its history. When J&J first announced that it would acquire Swiss medical device maker Synthes for $19.7 million in stock and cash, the firm indicated that the deal would dilute its current shareholders due to the issuance of 204 million new shares. Investors expressed their dismay by pushing the firm’s share price down immediately following the announcement. J&J looked for a way to make the deal more attractive to investors while preserving the composition of the purchase price paid to Synthes’ shareholders (two-thirds stock and the remainder in cash). They could defer the payment of taxes on that portion of the purchase price received in J&J shares until such shares were sold; however, they would incur an immediate tax liability on any cash received.

Having found a loophole in the IRS’s guidelines for utilizing funds held in foreign subsidiaries, J&J was able to make the deal’s financing structure accretive to earnings following closing. In 2011, the IRS had ruled that cash held in foreign operations repatriated to the United States would be considered a dividend paid by the subsidiary to the parent, subject to the appropriate tax rate. Because the United States has the highest corporate tax rate among developed countries, U.S. multinational firms have an incentive to reinvest earnings of their foreign subsidiaries abroad.

With this in mind, J&J used the foreign earnings held by its Irish subsidiary to buy 204 million of its own shares, valued at $12.9 billion, held by Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, which had previously acquired J&J shares in the open market. The buyback of J&J shares held by these investment banks increased the consolidated firm’s earnings per share. These shares, along with cash, were exchanged for outstanding Synthes’ shares to fund the transaction. J&J also avoided a hefty tax payment by not repatriating these earnings to the United States, where they would have been taxed at a 35% corporate rate rather than the 12% rate in Ireland. Investors reacted favorably, boosting J&J’s share price by more than 2% in mid-2012, when the firm announced the deal would be accretive rather than dilutive. Presumably, the IRS will move to prevent future deals from being financed in a similar manner.

Merck and Schering-Plough Merger: When Form Overrides Substance

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it really a duck? That is a question Johnson & Johnson might ask about a 2009 transaction involving pharmaceutical companies Merck and Schering-Plough. On August 7, 2009, shareholders of Merck and Company (“Merck”) and Schering-Plough Corp. (Schering-Plough) voted overwhelmingly to approve a $41.1 billion merger of the two firms. With annual revenues of $42.4 billion, the new Merck will be second in size only to global pharmaceutical powerhouse Pfizer Inc.

At closing on November 3, 2009, Schering-Plough shareholders received $10.50 and 0.5767 of a share of the common stock of the combined company for each share of Schering-Plough stock they held, and Merck shareholders received one share of common stock of the combined company for each share of Merck they held. Merck shareholders voted to approve the merger agreement, and Schering-Plough shareholders voted to approve both the merger agreement and the issuance of shares of common stock in the combined firms. Immediately after the merger, the former shareholders of Merck and Schering-Plough owned approximately 68 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of the shares of the combined companies.

The motivation for the merger reflects the potential for $3.5 billion in pretax annual cost savings, with Merck reducing its workforce by about 15 percent through facility consolidations, a highly complementary product offering, and the substantial number of new drugs under development at Schering-Plough. Furthermore, the deal increases Merck’s international presence, since 70 percent of Schering-Plough’s revenues come from abroad. The combined firms both focus on biologics (i.e., drugs derived from living organisms). The new firm has a product offering that is much more diversified than either firm had separately.

The deal structure involved a reverse merger, which allowed for a tax-free exchange of shares and for Schering-Plough to argue that it was the acquirer in this transaction. The importance of the latter point is explained in the following section.

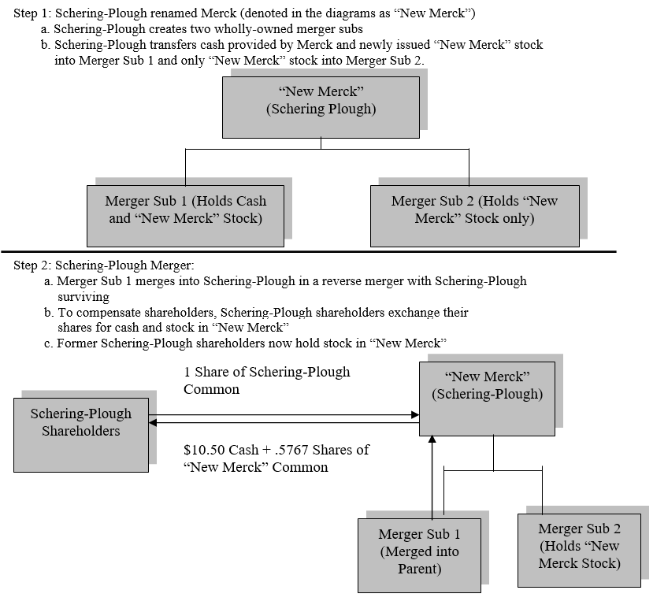

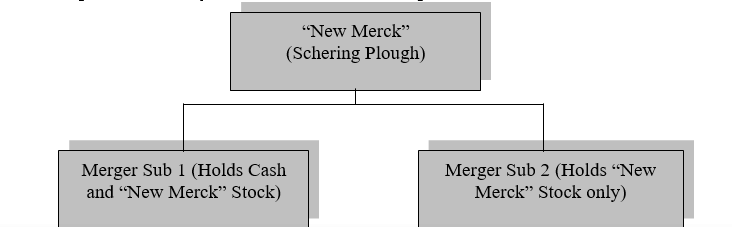

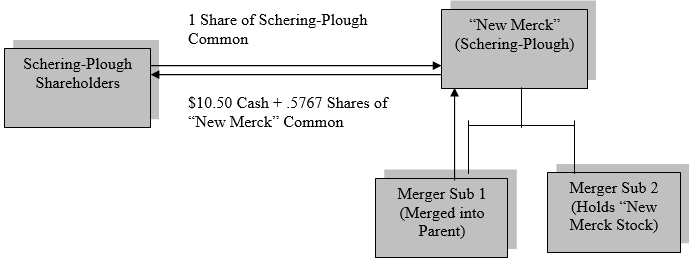

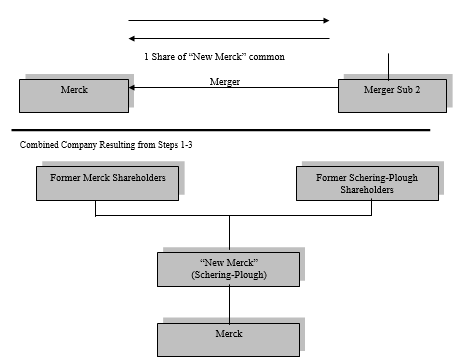

To implement the transaction, Schering-Plough created two merger subsidiaries (i.e., Merger Subs 1 and 2) and moved $10 billion in cash provided by Merck and 1.5 billion new shares (i.e., so-called “New Merck” shares approved by Schering-Plough shareholders) in the combined Schering-Plough and Merck companies into the subsidiaries. Merger Sub 1 was merged into Schering-Plough, with Schering-Plough the surviving firm. Merger Sub 2 was merged with Merck, with Merck surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Schering-Plough. The end result is the appearance that Schering-Plough (renamed Merck) acquired Merck through its wholly-owned subsidiary (Merger Sub 2). In reality, Merck acquired Schering-Plough.

Former shareholders of Schering-Plough and Merck become shareholders in the new Merck. The “New Merck” is simply Schering-Plough renamed Merck. This structure allows Schering-Plough to argue that no change in control occurred and that a termination clause in a partnership agreement with Johnson & Johnson should not be triggered. Under the agreement, J&J has the exclusive right to sell a rheumatoid arthritis drug it had developed called Remicade, and Schering-Plough has the exclusive right to sell the drug outside the United States, reflecting its stronger international distribution channel. If the change of control clause were triggered, rights to distribute the drug outside the United States would revert back to J&J. Remicade represented $2.1 billion or about 20 percent of Schering-Plough’s 2008 revenues and about 70 percent of the firm’s international revenues. Consequently, retaining these revenues following the merger was important to both Merck and Schering-Plough.

The multi-step process for implementing this transaction is illustrated in the following diagrams. From a legal perspective, all these actions occur concurrently.

Step 1: Schering-Plough renamed Merck (denoted in the diagrams as "New Merck")

a. Schering-Plough creates two wholly-owned merger subs

b. Schering-Plough transfers cash provided by Merck and newly issued "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 1 and only "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 2.

Step 2: Schering-Plough Merger:

a. Merger Sub 1 merges into Schering-Plough in a reverse merger with Schering-Plough surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Schering-Plough shareholders exchange their shares for cash and stock in "New Merck"

c. Former Schering-Plough shareholders now hold stock in "New Merck"

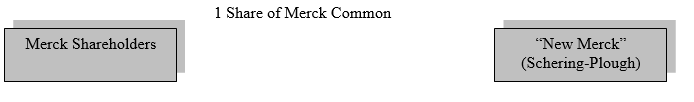

Step 3: Merck Merger:

a. Merger Sub 2 merges into Merck with Merck surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Merck shareholders exchange their shares for shares in "New Merck"

c. Former shareholders in Merck now hold shares in "New Merck" (i.e., a renamed Schering-Plough)

d, Merger Sub 2, a subsidiary of "New Merck," now owns Merck.

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck’s chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm’s board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough’s board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How might allowing the form of a transaction to override the actual spirit or intent of the deal impact the cost of doing business for the parties involved in the distribution agreement? Be specific.

Definitions:

Prescribing

The act of authorizing and advising the use of medical treatments, medications, or therapies by a healthcare professional.

Pharmacy

A location where prescription drugs are sold and advice on their safe use is provided; also refers to the branch of science concerned with the preparation, dispensing, and appropriate utilization of medication.

Situational Control

Fiedler’s classification of task characteristics in terms of how much control effective task performance requires.

Task Structure

A framework outlining how a task is organized, including its objectives, procedures, and evaluation criteria.

Q29: Using the M&A Valuation & Deal Structuring

Q30: The tax-free structure is generally not suitable

Q39: Both public and private firms always attempt

Q43: LBOs often exhibit very high financial returns

Q69: What are the common ways of estimating

Q91: In a balance sheet adjustment, the buyer

Q98: Which of the following is not true

Q108: A leveraged buyout initiated by a firm's

Q115: Pacific Surfware acquired Surferdude and as part

Q149: If two people exchange an apple, they