Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Pfizer Acquires Wyeth Labs Despite Tight Credit Markets

Pfizer and Wyeth began joint operations on October 22, 2009, when Wyeth shares stopped trading and each Wyeth share was converted to $33 in cash and 0.985 of a Pfizer share. Valued at $68 billion, the cash and stock deal was first announced in late January of 2009. The purchase price represented a 12.6 percent premium over Wyeth's closing share price the day before the announcement. Investors from both firms celebrated as Wyeth's shares rose 12.6 percent and Pfizer's 1.4 percent on the news. The announcement seemed to offer the potential for profit growth, despite storm clouds on the horizon.

As is true of other large pharmaceutical companies, Pfizer expects to experience serious erosion in revenue due to expiring patent protection on a number of its major drugs. Pfizer faced the expiration of patent rights in 2011 to the cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor, which accounted for 25 percent of the firm's $52 billion in 2008 revenue. Pfizer also faces 14 other patent expirations through 2014 on drugs that, in combination with Lipitor, contribute more than one-half of the firm's total revenue. Pfizer is not alone, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly are all facing significant revenue reduction due to patent expirations during the next five years as competition from generic drugs undercuts their pricing. Wyeth will also be losing its patent protection on its top-selling drug, the antidepressant Effexor XR.

Pfizer's strategy appears to have been to acquire Wyeth at a time when transaction prices were depressed because of the recession and tight credit markets. Pfizer anticipates saving more than $4 billion annually by combining the two businesses, with the savings being phased in over three years. Pfizer also hopes to offset revenue erosion due to patent expirations by diversifying into vaccines and arthritis treatments.

By the end of 2008, Pfizer already had a $22.5 billion commitment letter in order to obtain temporary or "bridge" financing and $26 billion in cash and marketable securities. Pfizer also announced plans to cut its quarterly dividend in half to $0.16 per share to help finance the transaction. However, there were still questions about the firm's ability to complete the transaction in view of the turmoil in the credit markets.

Many transactions that were announced during 2008 were never closed because buyers were unable to arrange financing and would later claim that the purchase agreement had been breached due to material adverse changes in the business climate. Such circumstances, they would argue, would force them to renege on their contracts. Usually, such contracts contain so-called reverse termination fees, in which the buyer would agree to pay a fee to the seller if they were unwilling to close the deal. This is called a reverse termination or breakup fee because traditionally breakup fees are paid by a seller that chooses to break a contract with a buyer in order to accept a more attractive offer from another suitor.

Negotiations, which had begun in earnest in late 2008, became increasingly contentious, not so much because of differences over price or strategy but rather under what circumstances Pfizer could back out of the deal. Under the terms of the final agreement, Pfizer would have been liable to pay Wyeth $4.5 billion if its credit rating dropped prior to closing and it could not finance the transaction. At about 6.6 percent of the purchase price, the termination fee was about twice the normal breakup fee for a transaction of this type.

What made this deal unique was that the failure to obtain financing as a pretext for exit could be claimed only under very limited circumstances. Specifically, Pfizer could renege only if its lenders refused to finance the transaction because of a credit downgrade of Pfizer. If lenders refused to finance primarily for this reason, Wyeth could either demand that Pfizer attempt to find alternative financing or terminate the agreement. If Wyeth had terminated the agreement, Pfizer would have been obligated to pay the termination fee.

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Using Form of Payment as a Takeover Strategy:

Chevron's Acquisition of Unocal

Unocal ceased to exist as an independent company on August 11, 2005 and its shares were de-listed from the New York Stock Exchange. The new firm is known as Chevron. In a highly politicized transaction, Chevron battled Chinese oil-producer, CNOOC, for almost four months for ownership of Unocal. A cash and stock bid by Chevron, the nation's second largest oil producer, made in April valued at $61 per share was accepted by the Unocal board when it appeared that CNOOC would not counter-bid. However, CNOOC soon followed with an all-cash bid of $67 per share. Chevron amended the merger agreement with a new cash and stock bid valued at $63 per share in late July. Despite the significant difference in the value of the two bids, the Unocal board recommended to its shareholders that they accept the amended Chevron bid in view of the growing doubt that U.S. regulatory authorities would approve a takeover by CNOOC.

In its strategy to win Unocal shareholder approval, Chevron offered Unocal shareholders three options for each of their shares: (1) $69 in cash, (2) 1.03 Chevron shares; or (3) .618 Chevron shares plus $27.60 in cash. Unocal shareholders not electing any specific option would receive the third option. Moreover, the all-cash and all-stock offers were subject to proration in order to preserve an overall per share mix of .618 of a share of Chevron common stock and $27.60 in cash for all of the 272 million outstanding shares of Unocal common stock. This mix of cash and stock provided a "blended" value of about $63 per share of Unocal common stock on the day that Unocal and Chevron entered into the amendment to the merger agreement on July 22, 2005. The "blended" rate was calculated by multiplying .618 by the value of Chevron stock on July 22nd of $57.28 plus $27.60 in cash. This resulted in a targeted purchase price that was about 56 percent Chevron stock and 44 percent cash.

This mix of cash and stock implied that Chevron would pay approximately $7.5 billion (i.e., $27.60 x 272 million Unocal shares outstanding) in cash and issue approximately 168 million shares of Chevron common stock (i.e., .618 x 272 million of Unocal shares) valued at $57.28 per share as of July 22, 2005. The implied value of the merger on that date was $17.1 billion (i.e., $27.60 x 272 million Unocal common shares outstanding plus $57.28 x 168 million Chevron common shares). An increase in Chevron's share price to $63.15 on August 10, 2005, the day of the Unocal shareholders' meeting, boosted the value of the deal to $18.1 billion.

Option (1) was intended to appeal to those Unocal shareholders who were attracted to CNOOC's all cash offer of $67 per share. Option (2) was designed for those shareholders interested in a tax-free exchange. Finally, it was anticipated that option (3) would attract those Unocal shareholders who were interested in cash but also wished to enjoy any appreciation in the stock of the combined companies.

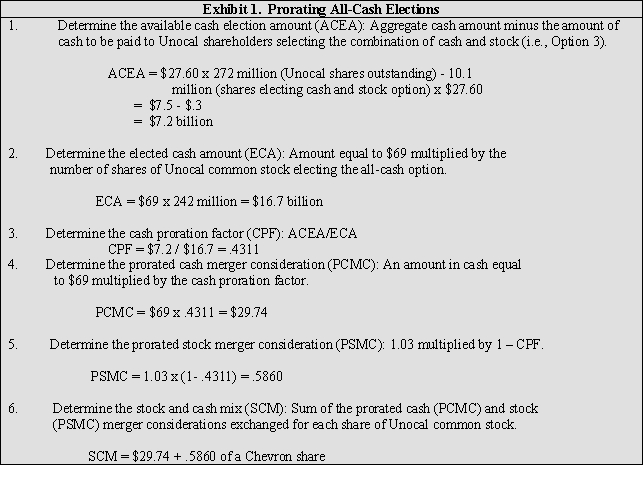

The agreement of purchase and sale between Chevron and Unocal contained a "proration clause." This clause enabled Chevron to limit the amount of total cash it would payout under those options involving cash that it had offered to Unocal shareholders and to maintain the "blended" rate of $63 it would pay for each share of Unocal stock. Approximately 242 million Unocal shareholders elected to receive all cash for their shares, 22.1 million opted for the all-stock alternative, and 10.1 million elected the cash and stock combination. No election was made for approximately .3 million shares. Based on these results, the amount of cash needed to satisfy the number shareholders electing the all-cash option far exceeded the amount that Chevron was willing to pay. Consequently, as permitted in the merger agreement, the all-cash offer was prorated resulting in the Unocal shareholders who had elected the all-cash option receiving a combination of cash and stock rather than $69 per share. The mix of cash and stock was calculated as shown in Exhibit 1.  If too many Unocal shareholders had elected to receive Chevron stock, those making the all-stock election would not have received 1.03 shares of Chevron stock for each share of Unocal stock. Rather, they would have received a mix of stock and cash to help preserve the approximate 56 percent stock and 44 percent cash composition of the purchase price desired by Chevron. For illustration only, assume the number of Unocal shares to be exchanged for the all-cash and all-stock options are 22.1 and 242 million, respectively. This is the reverse of what actually happened. The mix of stock and cash would have been prorated as shown in Exhibit 2.

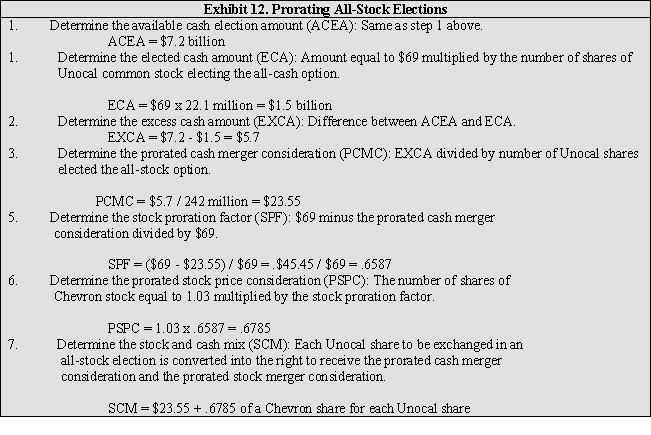

If too many Unocal shareholders had elected to receive Chevron stock, those making the all-stock election would not have received 1.03 shares of Chevron stock for each share of Unocal stock. Rather, they would have received a mix of stock and cash to help preserve the approximate 56 percent stock and 44 percent cash composition of the purchase price desired by Chevron. For illustration only, assume the number of Unocal shares to be exchanged for the all-cash and all-stock options are 22.1 and 242 million, respectively. This is the reverse of what actually happened. The mix of stock and cash would have been prorated as shown in Exhibit 2.  It is typical of large transactions in which the target has a large, diverse shareholder base that acquiring firms offer target shareholders a "menu" of alternative forms of payment. The objective is to enhance the likelihood of success by appealing to a broader group of shareholders. To the unsophisticated target shareholder, the array of options may prove appealing. However, it is likely that those electing all-cash or all-stock purchases are likely to be disappointed due to probable proration clauses in merger contracts. Such clauses enable the acquirer to maintain an overall mix of cash and stock in completing the transaction. This enables the acquirer to limit the amount of cash they must borrow or the number of new shares they must issue to levels they find acceptable.

It is typical of large transactions in which the target has a large, diverse shareholder base that acquiring firms offer target shareholders a "menu" of alternative forms of payment. The objective is to enhance the likelihood of success by appealing to a broader group of shareholders. To the unsophisticated target shareholder, the array of options may prove appealing. However, it is likely that those electing all-cash or all-stock purchases are likely to be disappointed due to probable proration clauses in merger contracts. Such clauses enable the acquirer to maintain an overall mix of cash and stock in completing the transaction. This enables the acquirer to limit the amount of cash they must borrow or the number of new shares they must issue to levels they find acceptable.

Discussion Questions

-How did Chevron use the form of payment as a potential takeover strategy?

Definitions:

Annual Salary Increases

Regular, incremental adjustments to an employee's base pay, typically conducted on a yearly basis to keep up with market rates, inflation, or to reward performance.

Flexible Work Hour Plans

Employment arrangements that allow workers to choose their work hours within specified limits.

Core Time

A period during the workday when all employees are expected to be at work, allowing for flexibility at the start and end of the day while ensuring a common time for collaboration.

Down Time

Periods when a machine, system, or employee is not productive, due to maintenance, repairs, or rest, which can impact overall operational efficiency.

Q37: The enterprise value to EBITDA method is

Q41: A cross-marketing relationship is one in which

Q42: Which of the following is not true

Q69: Given the terms of the agreement,Wrigley shareholders

Q71: Nontaxable transactions also are called tax-free reorganizations.

Q75: In determining the initial offer price,the acquirer

Q80: Joint ventures sometimes represent good alternatives to

Q84: What is the acquisition vehicle used to

Q89: The total value of the firm according

Q90: What are the primary differences between a