The General Motors’ Bankruptcy—The Largest Government-Sponsored Bailout in U.S. History

Rarely has a firm fallen as far and as fast as General Motors. Founded in 1908, GM dominated the car industry through the early 1950s with its share of the U.S. car market reaching 54 percent in 1954, which proved to be the firm’s high water mark. Efforts in the 1980s to cut costs by building brands on common platforms blurred their distinctiveness. Following increasing healthcare and pension benefits paid to employees, concessions made to unions in the early 1990s to pay workers even when their plants were shut down reduced the ability of the firm to adjust to changes in the cyclical car market. GM was increasingly burdened by so-called legacy costs (i.e., healthcare and pension obligations to a growing retiree population). Over time, GM’s labor costs soared compared to the firm’s major competitors. To cover these costs, GM continued to make higher margin medium to full-size cars and trucks, which in the wake of higher gas prices could only be sold with the help of highly attractive incentive programs. Forced to support an escalating array of brands, the firm was unable to provide sufficient marketing funds for any one of its brands.

With the onset of one of the worst global recessions in the post–World War II years, auto sales worldwide collapsed by the end of 2008. All automakers’ sales and cash flows plummeted. Unlike Ford, GM and Chrysler were unable to satisfy their financial obligations. The U.S. government, in an unprecedented move, agreed to lend GM and Chrysler $13 billion and $4 billion, respectively. The intent was to buy time to develop an appropriate restructuring plan.

Having essentially ruled out liquidation of GM and Chrysler, continued government financing was contingent on gaining major concessions from all major stakeholders such as lenders, suppliers, and labor unions. With car sales continuing to show harrowing double-digit year over year declines during the first half of 2009, the threat of bankruptcy was used to motivate the disparate parties to come to an agreement. With available cash running perilously low, Chrysler entered bankruptcy in early May and GM on June 1, with the government providing debtor in possession financing during their time in bankruptcy. In its bankruptcy filing for its U.S. and Canadian operations only, GM listed $82.3 billion in assets and $172.8 billion in liabilities. In less than 45 days each, both GM and Chrysler emerged from government-sponsored sales in bankruptcy court, a feat that many thought impossible.

Judge Robert E. Gerber of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court of New York approved the sale in view of the absence of alternatives considered more favorable to the government’s option. GM emerged from the protection of the court on July 10, 2009, in an economic environment characterized by escalating unemployment and eroding consumer income and confidence. Even with less debt and liabilities, fewer employees, the elimination of most “legacy costs,” and a reduced number of dealerships and brands, GM found itself operating in an environment in 2009 in which U.S. vehicle sales totaled an anemic 10.4 million units. This compared to more than 16 million in 2008. GM’s 2009 market share slipped to a post–World War II low of about 19 percent.

While the bankruptcy option had been under consideration for several months, its attraction grew as it became increasingly apparent that time was running out for the cash-strapped firm. Having determined from the outset that liquidation of GM either inside or outside of the protection of bankruptcy would not be considered, the government initially considered a prepackaged bankruptcy in which agreement is obtained among major stakeholders prior to filing for bankruptcy. The presumption is that since agreement with many parties had already been obtained, developing a plan of reorganization to emerge from Chapter 11 would move more quickly. However, this option was not pursued because of the concern that the public would simply view the post–Chapter 11 GM as simply a smaller version of its former self. The government in particular was seeking to position GM as an entirely new firm capable of profitably designing and building cars that the public wanted.

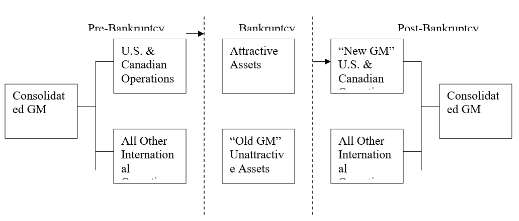

Time was of the essence. The concern was that consumers would not buy GM vehicles while the firm was in bankruptcy. Consequently, a strategy was devised in which GM would be divided into two firms: “old GM,” which would contain the firm’s unwanted assets, and “new GM,” which would own the most attractive assets. “New GM” would then emerge from bankruptcy in a sale to a new company owned by various stakeholder groups, including the U.S. and Canadian governments, a union trust fund, and bondholders. Only GM’s U.S. and Canadian operations were included in the bankruptcy filing. Figure 16.2 illustrates the GM bankruptcy process.

Buying distressed assets can be accomplished through a Chapter 11 plan of reorganization or a post-confirmation trustee. Alternatively, a 363 sale transfers the acquired assets free and clear of any liens, claims, and encumbrances. The sale of GM’s attractive assets to the “new GM” was ultimately completed under Section 363 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Historically, firms used this tactic to sell failing plants and redundant equipment. In recent years, so-called 363 sales have been used to completely restructure businesses, including the 363 sales of entire companies. A 363 sale requires only the approval of the bankruptcy judge, while a plan of reorganization in Chapter 11 must be approved by a substantial number of creditors and meet certain other requirements to be approved. A plan of reorganization is much more comprehensive than a 363 sale in addressing the overall financial situation of the debtor and how its exit strategy from bankruptcy will affect creditors. Once a 363 sale has been consummated and the purchase price paid, the bankruptcy court decides how the proceeds of sale are allocated among secured creditors with liens on the assets sold.

Total financing provided by the U.S. and Canadian (including the province of Ontario) governments amounted to $69.5 billion. U.S. taxpayer-provided financing totaled $60 billion, which consisted of $10 billion in loans and the remainder in equity. The government decided to contribute $50 billion in the form of equity to reduce the burden on GM of paying interest and principal on its outstanding debt. Nearly $20 billion was provided prior to the bankruptcy, $11 billion to finance the firm during the bankruptcy proceedings, and an additional $19 billion in late 2009. In exchange for these funds, the U.S. government owns 60.8 percent of the “new GM’s common shares, while the Canadian and Ontario governments own 11.7 percent in exchange for their investment of $9.5 billion. The United Auto Workers’ new voluntary employee beneficiary association (VEBA) received a 17.5 percent stake in exchange for assuming responsibility for retiree medical and pension obligations. Bondholders and other unsecured creditors received a 10 percent ownership position. The U.S. Treasury and the VEBA also received $2.1 billion and $6.5 billion in preferred shares, respectively.

The new firm, which employs 244,000 workers in 34 countries, intends to further reduce its head count of salaried employees to 27,200 by 2012. The firm will also have shed 21,000 union workers from the 54,000 UAW workers it employed prior to declaring bankruptcy in the United States and close 12 to 20 plants. GM did not include its foreign operations in Europe, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, or Asia Pacific in the Chapter 11 filing. Annual vehicle production capacity for the firm will decline to 10 million vehicles in 2012, compared with 15 to 17 million in 1995. The firm exited bankruptcy with consolidated debt at $17 billion and $9 billion in 9 percent preferred stock, which is payable on a quarterly basis. GM has a new board, with Canada and the UAW healthcare trust each having a seat on the board.

Following bankruptcy, GM has four core brands—Chevrolet, Cadillac, Buick, and GMC—that are sold through 3,600 dealerships, down from its existing 5,969-dealer network. The business plan calls for an IPO whose timing will depend on the firm’s return to sufficient profitability and stock market conditions.

By offloading worker healthcare liabilities to the VEBA trust and seeding it mostly with stock instead of cash, GM has eliminated the need to pay more than $4 billion annually in medical costs. Concessions made by the UAW before GM entered bankruptcy have made GM more competitive in terms of labor costs with Toyota.

Assets to be liquidated by Motors Liquidation Company (i.e., “old GM) were split into four trusts, including one financed by $536 million in existing loans from the federal government. These funds were set aside to clean up 50 million square feet of industrial manufacturing space at 127 locations spread across 14 states. Another $300 million was set aside for property taxes, plant security, and other shutdown expenses. A second trust will handle claims of the owners of GM’s prebankruptcy debt, who are expected to get 10 percent of the equity in General Motors when the firm goes public and warrants to buy additional shares at a later date. The remaining two trusts are intended to process litigation such as asbestos-related claims. The eventual sale of the remaining assets could take four years, with most of the environmental cleanup activities completed within a decade.

Reflecting the overall improvement in the U.S. economy and in its operating performance, GM repaid $10 billion in loans to the U.S. government in April 2010. Seventeen months after emerging from bankruptcy, the firm completed successfully the largest IPO in history on November 17, 2010, raising $23.1 billion. The IPO was intended to raise cash for the firm and to reduce the government’s ownership in the firm, reflecting the firm’s concern that ongoing government ownership hurt sales. Following completion of the IPO, government ownership of GM remained at 33 percent, with the government continuing to have three board representatives.

GM is likely to continue to receive government support for years to come. In an unusual move, GM was allowed to retain $45 billion in tax loss carryforwards, which will eliminate the firm’s tax payments for years to come. Normally, tax losses are preserved following bankruptcy only if the equity in the reorganized company goes to creditors who have been in place for at least 18 months. Despite not meeting this criterion, the Treasury simply overlooked these regulatory requirements in allowing these tax benefits to accrue to GM. Having repaid its outstanding debt to the government, GM continued to owe the U.S. government $36.4 billion ($50 billion less $13.6 billion received from the IPO) at the end of 2010. Assuming a corporate marginal tax rate of 35 percent, the government would lose another $15.75 in future tax payments as a result of the loss carryforward. The government also is providing $7,500 tax credits to buyers of GM’s new all-electric car, the Chevrolet Volt.

-Discuss the relative fairness to the various stakeholders in a bankruptcy of a

more traditional Chapter 11 bankruptcy in which a firm emerges from the protection of the bankruptcy court following the development of a plan of reorganization versus an expedited sale under Section 363 of the federal bankruptcy law. Be specific.

Definitions:

Law Defined

The system of rules created and enforced through social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior.

Bona Fide Occupational Requirement

A condition or requirement necessary for performing a job that can justify discrimination based on otherwise protected categories if it is genuinely needed to carry out job responsibilities.

Human Rights Legislation

Laws and statutes that protect individuals' fundamental rights and freedoms, typically enforced by national and international legal frameworks.

Rights Limited

Circumstances where the rights typically afforded to individuals or entities are restricted under certain conditions.

Q7: In an action research study,a researcher would

Q18: What type of ethical issues does collecting

Q18: A preliminary exploratory analysis of a qualitative

Q27: Who are the participants in the study?

Q29: What is the central phenomenon being studied?

Q41: What were the motivations for this deal

Q45: The new company,Chrysler Holdings,is a limited liability

Q83: Why would the buyout firms want Qwest

Q106: Which of the following is generally not

Q108: To decide if a business is worth